Last October 2013, while on a coin buying trip to the United Kingdom, I had the opportunity to visit two coin exhibits at the Tower of London. The first exhibit, called Coins and Kings: The Royal Mint at the Tower, is held in a small hall on the outer ward on Mint St, while the second exhibit occupies a floor in the White Tower itself, overlooking the inner courtyard on one side and the Thames on the other.

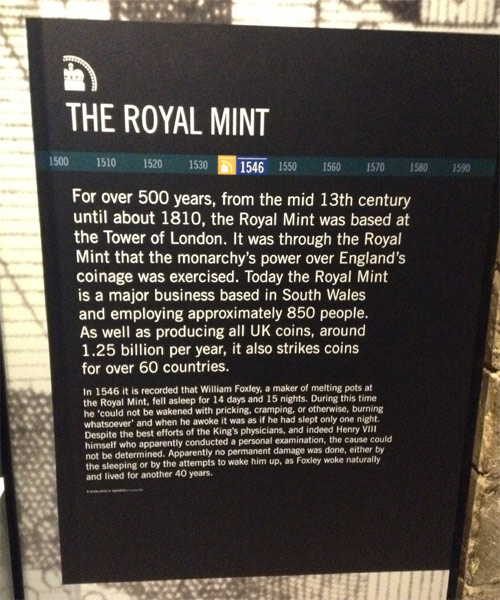

Most Australian coin collectors already know that the Royal Mint is the official mint of the United Kingdom. Fewer, however, would know that the Royal Mint used to reside in what is now a historic castle near the centre of London. The castle, known as the Tower of London, started off as an imposing fortification for Saxon London around the year 1100, but it wasn’t until around 1280 that the edifice was used as one of England’s mints. The following 650-odd years saw the production of millions of coins, and it wasn’t until the mid 20th century that coin manufacturing moved to a more modern facility in Llantrisant, South Wales, three hours away.

The entrance to the Coins and Kings exhibit.

I missed the Coins and Kings: The Royal Mint at the Tower exhibit the first time I visited the Tower in 2012. Mint St, the cobblestone path on which the exhibit is held, is a little bit off the beaten tourist track, and I would have missed it again had I not noticed it on the map. Upon entering the exhibit, which is enclosed in a small, high-roofed terrace just off the street, the first display described why the mint existed inside a castle, rather than, say, inside a factory or medieval warehouse. It turns out—rather obviously, in retrospect—that coins, like the kings themselves, needed the protection of a castle’s walls. If you knocked off a bag of twenty cent coins from the Royal Australian Mint in Canberra, it’d hardly be worth it, but back in medieval London, when coins were made of precious and semi-precious metals like gold and silver, a lifetime of wealth could be carried over the drawbridge in a sack.

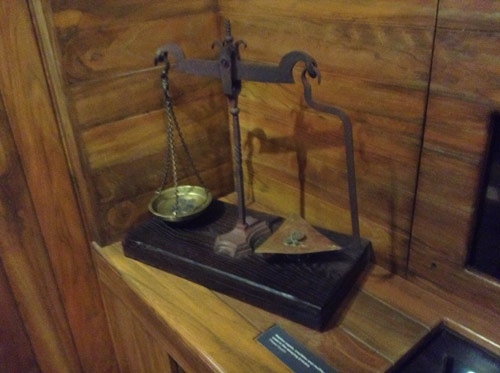

Coin scales

A pair of Edward II halfgroat dies.

Coin-related tools, including coin clipping shears, a small clipper, and a hammer.

There were also examples of some of the tools that die sinkers used to produce dies. Impressively, they had an original pair of Edward II halfgroat dies on display (as well as three halfgroats bearing the same designs as the dies). There was also a bit of a description on the process of “clipping”—both legal and illegal. A working pair of coin shearers was on display, which younger (or more enthusiastic) visitors could play with. Most interesting, of course, are the displays of actual valuable coins. After passing a short description of assaying during the Elizabethan period, I encountered a glass cabinet in the next room that contained an Elizabeth I sovereign, half pound, and crown, a Henry VIII testoon (a shilling) and groat (as well as equivalent examples that had been debased), as well as four silver and gold trial plates. (Trial plates were samples of metals that were compared to coins to test for purity and weight.) The room that followed contained a furnace. The description noted how the debased coinage of the late Henry VIII was remelted by her daughter, Elizabeth I, and reminted into purer coins with her portrait. The new purer coins helped to restore the faith in England’s coinage that had been lost by her father’s debased currency.

An Elizabethan I sovereign and a halfpound.

A coin furnace for smelting coins.

A Charles II portrait punch and reverse punch.

In the late 1600s, hammered coins gave way to machine-struck coins. The new screw presses produced far more regular-shaped coins, while their new milled edges discouraged illegal clipping. There was an example of a screw press in the next room, as well as an animated projection in the background demonstrating how the new milled coins were struck. The most impressive coin in this cabinet was a Charles II five guinea, one of the largest circulation gold coins in the world.

A manual screw press.

A tool box and a pair of coin scales.

It’s not widely known that Isaac Newton—the man who came up with the Universal Law of Gravitation after supposedly observing an apple fall from a tree—played an important role at the Royal Mint. After becoming the Warden of the mint in 1696, he used his mathematical skills to improve the efficiency of mint processes, according to a sign near the end of the exhibit. To emphasise the point, the exhibit presented a number of vintage scales and a small box of measuring equipment.

The coin display in the White Tower, Tower Hill.

A replica manual screw press.

The Coins and Kings exhibit ended with a small display of counterstamped US Liberty dollars, Spanish four and eight reals, and French five francs. Finally, there was a small display of counterfeit, clipped, and altered coins.

An obverse anvil die of a George II Five Guinea.

A reverse hammer die of a George II Five Guinea.

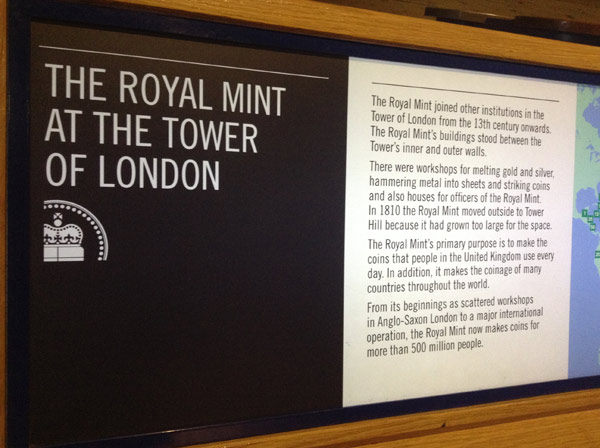

The second coin exhibit in Tower Hill was held in the White Tower itself. Although the Coins and Kings exhibit was touted as the major numismatic display in Tower Hill, the unnamed coin exhibit inside the While Tower was actually more impressive, in my opinion.

The coin exhibit in the White Tower.

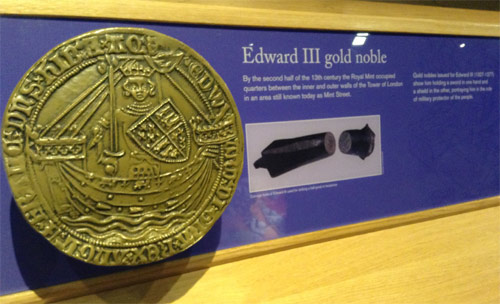

What caught my eye as soon as I walked into the long hall that contained the exhibit was a broad wall of coins, with each coin mounted in a sheet of green Perspex and individually described. There was a multitude of hammered silver and copper, as well as an impressive Elizabethan gold sovereign, a large Charles I silver crown, and an Edward III gold noble. No values were provided, but I have seen Elizabethan sovereigns sell in the five figures, while the noble was easily a $2,000 coin.

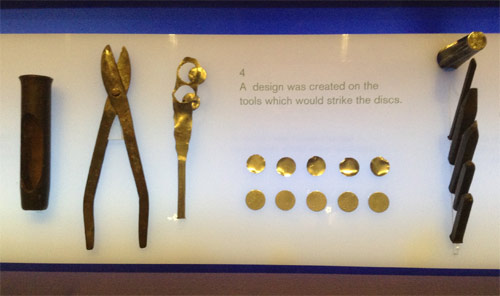

A coin cutter, a coin shearer, a cut sheet, and blanks.

Adjacent to the coin display was a reproduction of a screw press, which was used to strike the planchet with a design. The screw press, the man-operated predecessor to the steam-powered press, was made up of a long, weighted bar attached to a screw, which, in turn, was attached to a die that lowered and rose with the turning of the weighted bar. I spent several minutes examining the replica of the press on display, much to the curiosity of onlookers, and it became clear to me that screwing a design into the hot planchet would have been enormously hard work, even with the help of two or three additional men. The press on display had a pair of George IV five guinea dies, one obverse (the anvil die) and a reverse die (the hammer die). I wasn’t sure whether the dies were genuine or replicas, but they certainly looked genuine.

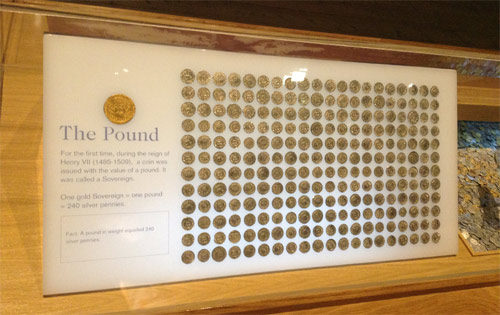

A gold pound and its equivalent in silver, 240 silver pennies

A Henry VII gold pound.

A pile of silver pennies and gold half pounds.

We entered the next room to be confronted by a very long, waist-high display that stretched about fifteen metres toward the end of the room. I could see what they were trying to do: It was a history of coinage that circulated since the early days of Tower Hill. Every five metres, an enlarged plaster copy of a specific coin was mounted next to a wonderfully anachronistic CRT computer screen. The screen displayed stylised photographs and videos of that coin, as well as re-enactments of how the coin might have been struck. Finally, next to the computer screen were two of the coins themselves, one showing the obverse and the other reverse.

The first coin was a silver penny from William I’s rule, 1066 - 1087. Although not struck at the mint in Tower Hill, the silver penny would have circulated when William I began the construction of the tower. Adjacent to the silver penny display was a large piece of cut timber on which was mounted a hammer and a pair of dies. The display was entitled Making money in the Middle Ages, and described how a lump of metal was flattened, sheared, hammered, and trimmed to transform it into coins. There was a display of dies next to their corresponding coins. I couldn’t tell if the coins (or dies) were original or reproductions, but they looked to have been made of gold. The following displays contained a Henry VII (1485 - 1509) gold “Tower” pound, an Edward VI gold sovereign, a George I and George II silver crown, and finally, a digital screen playing a video about the United Kingdom’s latest modern coins. Admittedly, jumping from a George II crown of 1727 - 1760 to modern fiat coinage of 2012 was a little jarring: After all, there was a good two hundred and fifty years of coinage in between (including my favourite coins, the modern gold sovereign, minted from 1817). I suspect the exhibit was trying to focus only on coins manufactured at Tower Hill.

Overall, both exhibits were impressive. The interactive machinery, coin tools, and computer screens were very interesting, while I spent most of my time on the displays of actual coins. It was a lot like a coin show, except that nothing was priced or for sale. I would certainly visit again, and if you happen to be in London, it’s certainly worth the train ride just outside to town to check it out. For more information about coins and Tower Hill, visit the Tower Hill website here.

Related links:

Change website currency

Change website currency

Comments